最新活動

本會消息

Latest馬來西亞女大生命案被告死刑判決撤銷發回之回應 及 相關媒體報導

by humanright | 4 月 23, 2025 | 本會消息

馬國女大生命案嫌犯三度判死撤銷 中華人權協會表遺憾 | 聯合新聞網震驚社會的長榮大學馬來西亞女學生命案,最高法院再度撤銷嫌犯梁育誌的死刑判決。中華人權協會對此表達遺憾,認為最高法院撤銷下…...

-

第19屆第三次會員大會 紀實

by humanright | 3 月 23, 2025 | 本會消息

-

第19屆第三次會員大會手冊

by humanright | 3 月 22, 2025 | 本會消息

-

2024 人權之夜 紀實

by humanright | 12 月 12, 2024 | 本會消息

-

「實質廢死」判決對社會帶來的影響與爭議 — 高思博理事長與吳宗憲立委記者會

by humanright | 11 月 30, 2024 | 本會消息

人權新聞

Latest-

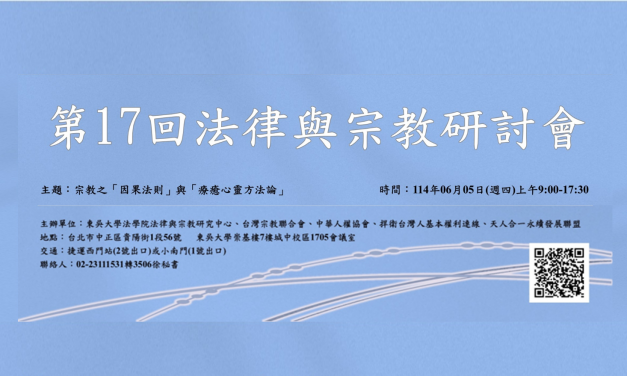

第 16 回 法律與宗教研討會

by humanright | 4 月 22, 2025 | 人權新聞

-

「賴十七條」的正當與合法性

by humanright | 3 月 18, 2025 | 人權新聞

-

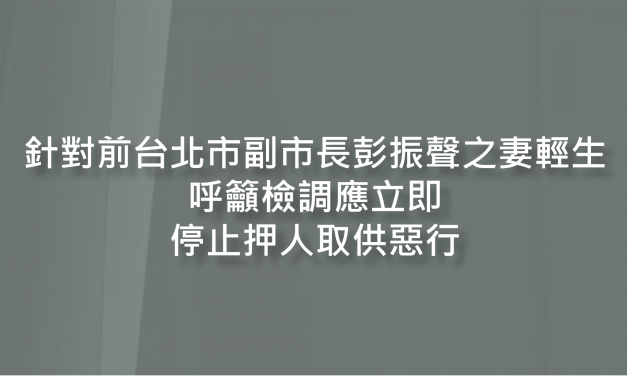

實質廢死 政治辦案 司法公信力雪崩

by humanright | 1 月 9, 2025 | 人權新聞

會員消息

Latest-

第 15 回 法律與宗教研討會

by humanright | 3 月 24, 2025 | 會員消息

-

感恩的人生與保障優質的人權志業而奔馳奮進~

by humanright | 3 月 23, 2025 | 會員消息

-

人權協會拜會最高檢察署,爭取犯罪被害人權益保障

by humanright | 3 月 17, 2025 | 會員消息